During the Depression, when casinos were legal in Mexico, my grandfather worked as a bookkeeper and cashier at a club in Mexicali. My grandparents lived across the border in Calexico. They were embarrassed that Grandpa was working at a casino, but it was a job. Although recreation was limited in Calexico, they found a surprising amount of entertainment in wandering the desert and examining mineral specimens. It was a hobby that required nothing more than a guidebook.

My grandparents never lost their interest in rocks and minerals. When they were prosperous, they invested in rock-cutting equipment and slabs of mineral specimens. They learned how to cut stones and make simple jewelry. They visited mineral shows and bought more specimens. They kept picking up rocks as they walked. On beach walks, they showed me how to identify feldspar by washing a rock in the surf, and then tilting it to look for a shiny glint. Beach rocks accumulated in a pile next to their patio.

Eventually, they weren’t able to walk on the beach or work with their rock-cutting equipment. They couldn’t bear disposing of the equipment and the mineral specimens that had cost them something in both money and thought. Their garage was full of rocks and their last car sat outside on the driveway. Grandma went first, and a few years later, Grandpa died in the armchair next to his view window.

“Many possessions hold an emotional charge.” photo Clutter 4 by Scott O’Donnell

My parents spent a month clearing out their home. They diligently found recipients for clothes, house wares, Grandpa’s record collection, the last car, and the organ wedged into the living room along with the grand piano. I can’t remember what my parents did with the minerals. They sold the house to a professor at San Diego State who completely redesigned it, taking advantage of the multi-level site to create a uniquely beautiful home.

Once they got over the shock, my grandparents would have liked this. They would have regarded the new owner as a kindred spirit, dedicated to making his home a place with a special feel. In its heyday, their more modest home was artistically arranged, and their home décor had a numinous quality. I have a few of their knick knacks, but the magic is gone from them. They are pretty, but they mean less now.

“The sense of emotional loss when we dispose of possessions isn’t trivial.” photo Clutter 5 by Scott O’Donnell

When I stop to examine a rock, I remember the connection to my grandparents, and of course rocks are abundant and free. I don’t collect them, but they give me a particular pleasure.

Like most Americans, I have many possessions that hold an emotional charge. Recently, I hesitated before tossing an old plastic beverage container into the recycling bin. Why? The beverage container was a reminder of the days when my children were small, and we often played and picnicked in parks. I feared I would lose those memories if I no longer owned that container.

“Things may be all we have to remind us of family, where we were raised, what we hold dear, and when we were happiest.” photo Clutter 6 (creepy doll) by Scott O’Donnell. All four of O’Donnell’s “Clutter” photos, including the initial full-house image, were taken in rural Pennsylvania and are used by permission under Creative Commons license.

The sense of emotional loss when we dispose of possessions isn’t trivial. Things may be all we have to remind us of family, where we were raised, what we hold dear, and when we were happiest.

We obtain things almost without thought. Managing the flow in and out of a household takes constant effort, and when emotional logjams are in place, we have overflowing cupboards, bulging garages and self-storage unit bills. Dave Bruno’s One Hundred Thing Challengemay seem contrived, but I think the book is worthwhile because it’s easy to read and presents Bruno’s internal struggles with his materialism simply and clearly.

Bruno decided he was “stuck in stuff” and challenged himself to limit his personal possessions to 100 items. Perhaps he cheated by counting his sock supply as one item, but I think that is being picky. As he describes letting go of hobby items and sports gear, he gets at the heart of the matter: decoupling the meaning of his life from his things. Once he realizes that his high quality, but rarely-used woodworking tools aren’t bringing him fulfillment, he can let them go.

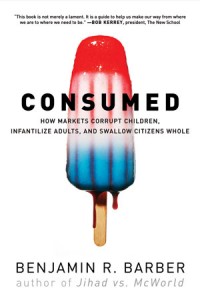

Bruno lives in San Diego, a setting he labels as “paradise.” A short distance away in Mexico, living standards are lower. Benjamin Barber addresses this global justice issue in Consumed. According to Barber, the developed world is choking on an excess of consumer products produced by the capitalist economy. Somehow, the system can’t be adjusted so that people in Africa, for example, have jobs and can afford the goods and community services, like clean water, that would life them out of poverty. Ironically, Dave Bruno designs the 100 thing challenge in San Diego while a family in Tijuana can’t afford to send their children to school. Barber’s point is that consumer capitalism infantilizes people as they mindlessly gratify themselves with shopping and lose the perspective necessary to make them responsible citizens, locally and globally.

The exact mechanism of getting people to buy more than they should is examined in Juliet Schor’s The Overspent American. Although this book was published in 1998, Schor’s description of how people aspire to mass media ideals of consumption continues to be relevant. Schor shows how people compare themselves less with their neighbors and more with media images of extreme affluence, propelling them into debt-based living.

The Overspent American and Consumed will be appreciated by sociology majors. Spent, by Avis Cardella, speaks powerfully to anyone who enjoys shopping. It’s easy to stereotype shopping addicts as fashion victims, but Cardella’s intelligent, restrained description of her self-destructive behavior shows how hard it was to resist. Particularly disturbing is her detailed recall of specific purchases, mostly made against her better judgment, over a period of two decades. Cardella’s life was defined by the contents of her closet.

Living Large,by Sarah Wexler, is entertaining journalism about big stuff: McMansions, enormous engagement rings, surgically enhanced breasts, Hummers, and giant landfills. She raises serious questions without scolding Americans for loving bigness. The chapter on landfills made me uncomfortable about being part of the problem. According to Wexler, an island of plastic refuse has gradually accumulated in the Pacific, an ominous monument to consumerism.

Sadly, dumpsters overflow with stuff tossed by “Boomer” children of parents who learned frugality in the Depression. People who kept canning jars and brown paper grocery bags were overwhelmed by the explosion of plastic in the years following World War II. Julie Hall, the “estate lady” says she has thrown out countless Cool Whip containers. Hall, the author of The Boomer Burden and several other books on disposing of a deceased family member’s estate, has practical suggestions on splitting valuables among family members, selling valuable and not-so-valuable heirlooms, and coping with the emotional overload of sorting through a loved one’s home.

After reading The Boomer Burden I managed to discard some things, the low-hanging fruit, so to speak. My home looks as cluttered as ever. I have a long ways to go, but I find I enjoy getting rid of things that were subconsciously worrying me simply by being in the house. Knowing that I have drawers and shelves of inactive stuff, I worry. What is it? What is it for? How will I use it? When it’s gone, I don’t have to think about it anymore, except to regret that some of it may last a thousand years in the local landfill.

Linda Worden is a Chico native now living with her husband and children in Boise, Idaho. In addition to discarding objects Linda also loves to read. Look for more of her book reviews in coming issues of Up the Road.

The Stuff of Life

During the Depression, when casinos were legal in Mexico, my grandfather worked as a bookkeeper and cashier at a club in Mexicali. My grandparents lived across the border in Calexico. They were embarrassed that Grandpa was working at a casino, but it was a job. Although recreation was limited in Calexico, they found a surprising amount of entertainment in wandering the desert and examining mineral specimens. It was a hobby that required nothing more than a guidebook.

My grandparents never lost their interest in rocks and minerals. When they were prosperous, they invested in rock-cutting equipment and slabs of mineral specimens. They learned how to cut stones and make simple jewelry. They visited mineral shows and bought more specimens. They kept picking up rocks as they walked. On beach walks, they showed me how to identify feldspar by washing a rock in the surf, and then tilting it to look for a shiny glint. Beach rocks accumulated in a pile next to their patio.

Eventually, they weren’t able to walk on the beach or work with their rock-cutting equipment. They couldn’t bear disposing of the equipment and the mineral specimens that had cost them something in both money and thought. Their garage was full of rocks and their last car sat outside on the driveway. Grandma went first, and a few years later, Grandpa died in the armchair next to his view window.

“Many possessions hold an emotional charge.” photo Clutter 4 by Scott O’Donnell

My parents spent a month clearing out their home. They diligently found recipients for clothes, house wares, Grandpa’s record collection, the last car, and the organ wedged into the living room along with the grand piano. I can’t remember what my parents did with the minerals. They sold the house to a professor at San Diego State who completely redesigned it, taking advantage of the multi-level site to create a uniquely beautiful home.

Once they got over the shock, my grandparents would have liked this. They would have regarded the new owner as a kindred spirit, dedicated to making his home a place with a special feel. In its heyday, their more modest home was artistically arranged, and their home décor had a numinous quality. I have a few of their knick knacks, but the magic is gone from them. They are pretty, but they mean less now.

“The sense of emotional loss when we dispose of possessions isn’t trivial.” photo Clutter 5 by Scott O’Donnell

When I stop to examine a rock, I remember the connection to my grandparents, and of course rocks are abundant and free. I don’t collect them, but they give me a particular pleasure.

Like most Americans, I have many possessions that hold an emotional charge. Recently, I hesitated before tossing an old plastic beverage container into the recycling bin. Why? The beverage container was a reminder of the days when my children were small, and we often played and picnicked in parks. I feared I would lose those memories if I no longer owned that container.

“Things may be all we have to remind us of family, where we were raised, what we hold dear, and when we were happiest.” photo Clutter 6 (creepy doll) by Scott O’Donnell. All four of O’Donnell’s “Clutter” photos, including the initial full-house image, were taken in rural Pennsylvania and are used by permission under Creative Commons license.

The sense of emotional loss when we dispose of possessions isn’t trivial. Things may be all we have to remind us of family, where we were raised, what we hold dear, and when we were happiest.

Bruno decided he was “stuck in stuff” and challenged himself to limit his personal possessions to 100 items. Perhaps he cheated by counting his sock supply as one item, but I think that is being picky. As he describes letting go of hobby items and sports gear, he gets at the heart of the matter: decoupling the meaning of his life from his things. Once he realizes that his high quality, but rarely-used woodworking tools aren’t bringing him fulfillment, he can let them go.

Bruno lives in San Diego, a setting he labels as “paradise.” A short distance away in Mexico, living standards are lower. Benjamin Barber addresses this global justice issue in Consumed. According to Barber, the developed world is choking on an excess of consumer products produced by the capitalist economy. Somehow, the system can’t be adjusted so that people in Africa, for example, have jobs and can afford the goods and community services, like clean water, that would life them out of poverty. Ironically, Dave Bruno designs the 100 thing challenge in San Diego while a family in Tijuana can’t afford to send their children to school. Barber’s point is that consumer capitalism infantilizes people as they mindlessly gratify themselves with shopping and lose the perspective necessary to make them responsible citizens, locally and globally.

The Overspent American and Consumed will be appreciated by sociology majors. Spent, by Avis Cardella, speaks powerfully to anyone who enjoys shopping. It’s easy to stereotype shopping addicts as fashion victims, but Cardella’s intelligent, restrained description of her self-destructive behavior shows how hard it was to resist. Particularly disturbing is her detailed recall of specific purchases, mostly made against her better judgment, over a period of two decades. Cardella’s life was defined by the contents of her closet.

Sadly, dumpsters overflow with stuff tossed by “Boomer” children of parents who learned frugality in the Depression. People who kept canning jars and brown paper grocery bags were overwhelmed by the explosion of plastic in the years following World War II. Julie Hall, the “estate lady” says she has thrown out countless Cool Whip containers. Hall, the author of The Boomer Burden and several other books on disposing of a deceased family member’s estate, has practical suggestions on splitting valuables among family members, selling valuable and not-so-valuable heirlooms, and coping with the emotional overload of sorting through a loved one’s home.

Sustainability note: I obtained all the books referenced above through my local library. Used copies are available through Amazon. Author Web sites are: benjaminbarber.com, guynameddave.com, aviscardella.com, julietschor.org, theestatelady.com, sarahzoewexler.com.

Linda Worden is a Chico native now living with her husband and children in Boise, Idaho. In addition to discarding objects Linda also loves to read. Look for more of her book reviews in coming issues of Up the Road.