Stuff to read, stuff to give to others to read—let’s hope for a few moments of peace to enjoy a book during the holiday season, and then stretch that peace as far into winter as we can. One woman spent an entire year reading a different book every day. At the end of the year, she wrote her own book.

After Nina Sankovitch’s sister died of cancer, she buried her grief in frantic activity. Until she sat down each day and simply read, she wasn’t able to come to terms with her sister’s death. As she read, she grieved not only her sister’s death, but also the family tragedies her parents experienced during World War II in Europe. Tolstoy and the Purple Chair: My Year of Magical Reading (Nina Sankovitch) chronicles her reading, and lists each of the 365 books she read during the year she devoted both to mourning and to connecting with literature on all levels, from the most serious fiction to crowd-pleasers like murder mysteries. If you don’t already know how, you can learn how to read all day from Sankovitch’s blog.

We all worry about overeating during the holidays. Maybe these urges to over-indulge can be satisfied by reading about eating. The Hanna Swenson mysteries(a series by Joanne Fluke) feature a cookie-baking detective and loads of excellent recipes. See the website for killer baking ideas.

The last Chinese emperor also had a cook. The Last Chinese Chef (Nicole Mones) describes Chinese cooking in exquisite detail. The reader will long to schedule a gourmet’s tour of China.

Following the Occupy Wall Street movement? Get some essential background in Charles R. Morris’ lucid explanation of the financial crises in The Two Trillion Dollar Meltdown, available as an ebook.

—Linda Worden

Just My Type(Simon Garfield)

OK, all you font geeks, here’s a quiz to whet your interest in one of 2011’s most entertaining books of nonfiction:

1. Which type designer wrote extensively in his diaries about his incestuous affairs and zoophilia?

2. “Friends don’t let friends set [which font?].” –Frank Romano, type scholar

3. Which German font was in the late ’50s briefly and with no apparent sense of irony considered for use on roadway signage between London and Yorkshire?

4. Which font appears more than any other in posters for Russell Crowe movies?

5. Which of the Ten Commandments was printed with a most unfortunate typo in Christopher Barker’s Bible of 1631, and how did it read?

If fonts have a Chaucer, it’s Simon Garfield. Just My Type (Gotham Books) is his detailed, amusing collection of stories about the letters and symbols we are surrounded by—who designed them and why, which are most and least popular, and what they’re good or not so good for. You may have read that comic sans is loathed by more designers than any other font, but did you know that courier may be the best font to use in a break-up letter if you think your soon-to-be ex really needs to get the message? Or that the ampersand in Garamond italics might just be the loveliest ampersand of all time? Go ahead and type it right now, then let Garfield tell you why that is.

With a lively foreword by acclaimed book designer Chip Kidd and a “periodic table of type” adorning the inside covers, Just My Type is just the thing for anyone who wants to know more about fonts.

—Beth Spencer

Answers to quiz: 1) Eric Gill 2) Souvenir 3) Akzidenz Grotesk 4) Trajan 5) The seventh: Thou Shalt Commit Adultery.

Of A Feather (Scott Weidensaul)

There is something like one bird book published every day in the United States. Look in your local bookstore and you’ll find a plethora of titles. I gave a quick perusal of Amazon.com and quickly found 432 books on hummingbirds alone. There were more; I just got tired of scrolling down the page.

There are a variety of books about birds – field guides (e.g. Birds of the West Indies), natural history (The Bird: A Natural History of Who Birds Are, Where They Came From, and How They Live), entertaining (my own Amazing Birds), art (The Art of Ornithology), scientific (The Singing Life of Birds: The Art and Science of Listening to Birdsong), major treatises (Handbook of Birds of the World, 16 Volumes), and a lot of minor and local publications (Birds of Bidwell Park, me again). I’ve read or at least consulted many, many bird-themed books over the years and can tell you that the quality of the writing and information varies widely, ranging from outstanding to what were the publishers thinking? Soaring With Fidel, about Osprey migration, gets some good reviews but I found it pretty darn boring.

In 2000 author Scott Weidensaul came out with Living on the Wind: Across the Hemisphere With Migratory Birds. Well researched and well written, it was a treat for me as a professional ornithologist to read but it is certainly accessible to anyone else. In 2008, he published Of A Feather, the history of birdwatching. From a review of this book in Goodreads.com:

“Arriving in the New World, Europeans were awestruck by a continent awash with birds. Today tens of millions of Americans birders have made a once eccentric hobby into something so mainstream it’s (almost) cool. Scott Weidensaul traces the colorful evolution of American birding: from the frontier ornithologists who collected eggs between border skirmishes to the society matrons who organized the first effective conservation movement; from the luminaries with checkered pasts, such as convicted blackmailer Alexander Wilson and the endlessly self-mythologizing John James Audubon, to the awkward schoolteacher Roger Tory Peterson, whose A Field Guide to the Birds prompted the explosive growth of modern birding. Spirited and compulsively readable, Of a Feather celebrates the passions and achievements of birders throughout American history.”

If it weren’t for the fact that this author had already impressed me, I would not have picked up this book. I’ve read too many dry tales of early ornithologists. But Of a Feather is exceptional and a treat to read.

—Roger Lederer

The Help(Kathryn Stockett)

The year is 1962. Miss Skeeter Phelan has graduated from Ole Miss University and returned home to Jackson, Mississippi for the summer. Her mother is nagging her to find a respectable job and/or a husband. Being a writer is Skeeter’s aim—to her mother’s dismay, much more important than a husband.

To escape her mother’s criticism Skeeter gets a job writing the household hints column for the local newspaper, this despite the fact that she has never done even one household chore. She turns for help to the Black maid of one of her best friends. From this unusual relationship comes Skeeter’s idea for a book: What do Black women think of the white families they work for? Skeeter at first does not realize how dangerous her project will become—both for her and the Black maids she enlists to share their stories. But at least such an idea fits what an editor at Harper & Row has told her:

“Don’t waste your time on obvious things. Write about what disturbs you, particularly if it bothers no one else.”

So this is the premise of Kathryn Stockett’s debut novel. Skeeter is writing a book about Black maids in the South in the 1960s, a book to be titled The Help. Stockett is writing her novel (The Help) about Skeeter’s experience. This double layer gives the novel extra complexity: When is Skeeter speaking? When is Stockett? And why did each choose that title?

For Skeeter, it’s because that’s how she naturally views maids, including her family’s “help” Constantine, nanny as well as maid, who raised her from birth. These women are not defined by their characters or their spirits, but by their general job description. Stockett’s identical title choice is not so naïve. Rather, she is examining how White families of Jackson, Mississippi (and many other Southern families of that era) viewed their servants. Not as individuals worthy of respect and concern but as solutions for a family’s needs—“the help.”

What does it mean when we reduce people to their function? In Stockett’s novel, Skeeter is astonished to discover that Aibileen—the first maid to help her—has read Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, a book she herself has not yet read. We learn about another maid, Minny, who twice saves her boss’s life even though originally she had no respect for this woman, who she viewed as lazy white trash. These invisible women, “the help,” and others like them are brave enough to risk their jobs and even their lives to tell their stories. Skeeter’s book powerfully supports their individuality. Even though they must remain anonymous, they are no longer just “the help.” Ultimately, this is the message of both books.

—Jo Ellen Hall

The Ecology of Hope(Ted Bernard and Jora Young)

Hope and Hard Times (Ted Bernard)

Two books “speak to my condition” as a person who cherishes both the earth’s natural webs of meaning—creatures, forests, rivers, and seasons—and its human inhabitants.

In the first book, The Ecology of Hope (1997), authors Ted Bernard and Jora Young seek out and report on inspiring developments in eight locations across America where communities have undertaken to “Collaborate For Sustainability,” as their subtitle declares. The narratives are compelling, well written, and accessible. Extra helpful are the maps.

Eight collaborations, from Monhegan Island, Maine and Menominee, Wisconsin, to Chicago and northern California, show how groups holding differing views and values and conflicting agendas somehow manage to sit down around a table of “gathered stakeholders to put aside historical differences, to work collaboratively, and to arrive at decisions consensually.”

The inclusion of a foreword by Wes Jackson signals the holistic sensibility adopted by Bernard and Young in their study. Two of the eight situations they report on are literally “up the road” in northern California: the Mattole Watershed on the “lost coast” of Humboldt County and the by-now well known efforts of the Quincy Library Group (loggers and environmentalist) to talk across economic and ecological interests toward collaboration. Jackson says the stories reported here “describe small and modest efforts—exactly the requirement for getting something done.” The authors’ informed and sensitive work in the field lays a solid foundation for the thesis of their book. Including epigrams and brief quotations by eloquent poets and thinkers enriches their narrative immensely.

The second book, by Bernard alone, follows up on the earlier study and reports on some added ones. Hope and Hard Times (2010) reports Bernard’s sober appreciation of the complexities and accidents that test the hopefulness and tenacity of good-hearted agents of change “when faced with ‘perilous voices’ of destruction, angry protests and legal action.” The agents of change Bernard values are “an unexpected collection of everyday Americans—folk from the nonprofit world, householders, working people, business people, bankers, farmers and ranchers, Native people, local government folk, even resource professionals from federal and state agencies.”

He is clear-eyed about the challenge of remaining hopeful given “the incredibly volatile situation in which we seem trapped: a scary combination of ticking environmental time bomb and a world financial meltdown.”

“My own sense is soberly sanguine,” Bernard confesses. “It derives not only from the hearts and works of the people in these stories but also from my long engagement with young minds who continue to come up with brilliant ways to tackle problems bequeathed by my generation.” He draws hope from “such visionaries as Henry David Thoreau, John Muir, Rachel Carson, Aldo Leopold, and, I will say, some of the unheralded dreamers in the stories that follow.”

Dreams are what we live on, what impel us up the road to better, healthier ways of living on the land, with the land. Castles in the air? That’s where they belong, Thoreau reminds us in Walden’s concluding chapter; “Now put the foundations under them,” he advises.

—David Wilson

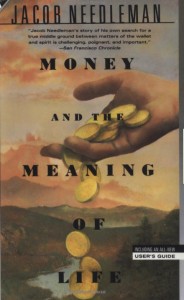

Money and the Meaning of Life(Jacob Needleman)

I know, I know. What a grinch I am to even bring up the subject of money in December, the height of America’s materialistic merry-making. Hasn’t it been a rough enough year already money-wise? you no doubt ask.

Well, yes, it has been rough for some of us, including me. That’s precisely the reason for mentioning this book, and doing it now. Money and the Meaning of Life by Jacob Needleman, published 20 years ago, offers some precious insight into where western civilization went so wrong in weighing up the relative worth of money and meaning. Not knowing, then, what we now know—again—about this country’s eagerness to dive headlong into greed, Needleman is free to explore the underlying reasons without having to spend half the book on current events.

You might blame it on the Protestant Reformation—or what came after, to be fair about it, how those new ideas played out culturally. This territory is probably old hat to many of you, but science and English major that I am, it was news to me. Good news, really, because his explanation makes so much sense. It’s not as if western values only recently became unhinged.

As Needleman explains it, early medieval Christianity was clear on the concept that money and material concerns were not evil so much as they were secondary, commerce being a natural outgrowth of man’s interdependent community relationships. But to value money beyond that—and to seek to acquire vast wealth, to view oneself as autonomous and self-sufficient—demonstrated the sin of pride, believing that one could live without breathing “the air of God.”

Protestants put forth the radical notion that humanity no longer needed to pay homage or bow down to earthly spiritual institutions and their rules. People could instead be guided by their own reason—and the word, the Bible, which believers could read and interpret for themselves. The whole world was declared holy, and any man’s calling in life as sacred as any priest’s. Money, along with whatever one’s work was in the world, were the tools of holiness. In Protestantism money and one’s work in the world were intended to be servants of the spiritual.

Yet the material separated from the spiritual yet again. Modern capitalism, science, and psychology all grew from this new, reason-based spiritual root. According to Max Weber, early twentieth-century sociologist, this new form of Christianity was partially responsible.

There’s more here, too, much more, from Maimonides to samsara. If you can find this book, I highly recommend it for kick-starting some deeper thinking about connections between the spiritual and material. If you can’t find it, maybe I’ll lend you my copy.

Eat, Read, Eat for the Holidays

Stuff to read, stuff to give to others to read—let’s hope for a few moments of peace to enjoy a book during the holiday season, and then stretch that peace as far into winter as we can. One woman spent an entire year reading a different book every day. At the end of the year, she wrote her own book.

After Nina Sankovitch’s sister died of cancer, she buried her grief in frantic activity. Until she sat down each day and simply read, she wasn’t able to come to terms with her sister’s death. As she read, she grieved not only her sister’s death, but also the family tragedies her parents experienced during World War II in Europe. Tolstoy and the Purple Chair: My Year of Magical Reading (Nina Sankovitch) chronicles her reading, and lists each of the 365 books she read during the year she devoted both to mourning and to connecting with literature on all levels, from the most serious fiction to crowd-pleasers like murder mysteries. If you don’t already know how, you can learn how to read all day from Sankovitch’s blog.

We all worry about overeating during the holidays. Maybe these urges to over-indulge can be satisfied by reading about eating. The Hanna Swenson mysteries (a series by Joanne Fluke) feature a cookie-baking detective and loads of excellent recipes. See the website for killer baking ideas.

The last Chinese emperor also had a cook. The Last Chinese Chef (Nicole Mones) describes Chinese cooking in exquisite detail. The reader will long to schedule a gourmet’s tour of China.

Following the Occupy Wall Street movement? Get some essential background in Charles R. Morris’ lucid explanation of the financial crises in The Two Trillion Dollar Meltdown, available as an ebook.

—Linda Worden

Just My Type (Simon Garfield)

OK, all you font geeks, here’s a quiz to whet your interest in one of 2011’s most entertaining books of nonfiction:

1. Which type designer wrote extensively in his diaries about his incestuous affairs and zoophilia?

2. “Friends don’t let friends set [which font?].” –Frank Romano, type scholar

3. Which German font was in the late ’50s briefly and with no apparent sense of irony considered for use on roadway signage between London and Yorkshire?

4. Which font appears more than any other in posters for Russell Crowe movies?

5. Which of the Ten Commandments was printed with a most unfortunate typo in Christopher Barker’s Bible of 1631, and how did it read?

If fonts have a Chaucer, it’s Simon Garfield. Just My Type (Gotham Books) is his detailed, amusing collection of stories about the letters and symbols we are surrounded by—who designed them and why, which are most and least popular, and what they’re good or not so good for. You may have read that comic sans is loathed by more designers than any other font, but did you know that courier may be the best font to use in a break-up letter if you think your soon-to-be ex really needs to get the message? Or that the ampersand in Garamond italics might just be the loveliest ampersand of all time? Go ahead and type it right now, then let Garfield tell you why that is.

With a lively foreword by acclaimed book designer Chip Kidd and a “periodic table of type” adorning the inside covers, Just My Type is just the thing for anyone who wants to know more about fonts.

—Beth Spencer

Answers to quiz: 1) Eric Gill 2) Souvenir 3) Akzidenz Grotesk 4) Trajan 5) The seventh: Thou Shalt Commit Adultery.

Of A Feather (Scott Weidensaul)

There is something like one bird book published every day in the United States. Look in your local bookstore and you’ll find a plethora of titles. I gave a quick perusal of Amazon.com and quickly found 432 books on hummingbirds alone. There were more; I just got tired of scrolling down the page.

There are a variety of books about birds – field guides (e.g. Birds of the West Indies), natural history (The Bird: A Natural History of Who Birds Are, Where They Came From, and How They Live), entertaining (my own Amazing Birds), art (The Art of Ornithology), scientific (The Singing Life of Birds: The Art and Science of Listening to Birdsong), major treatises (Handbook of Birds of the World, 16 Volumes), and a lot of minor and local publications (Birds of Bidwell Park, me again). I’ve read or at least consulted many, many bird-themed books over the years and can tell you that the quality of the writing and information varies widely, ranging from outstanding to what were the publishers thinking? Soaring With Fidel, about Osprey migration, gets some good reviews but I found it pretty darn boring.

In 2000 author Scott Weidensaul came out with Living on the Wind: Across the Hemisphere With Migratory Birds. Well researched and well written, it was a treat for me as a professional ornithologist to read but it is certainly accessible to anyone else. In 2008, he published Of A Feather, the history of birdwatching. From a review of this book in Goodreads.com:

“Arriving in the New World, Europeans were awestruck by a continent awash with birds. Today tens of millions of Americans birders have made a once eccentric hobby into something so mainstream it’s (almost) cool. Scott Weidensaul traces the colorful evolution of American birding: from the frontier ornithologists who collected eggs between border skirmishes to the society matrons who organized the first effective conservation movement; from the luminaries with checkered pasts, such as convicted blackmailer Alexander Wilson and the endlessly self-mythologizing John James Audubon, to the awkward schoolteacher Roger Tory Peterson, whose A Field Guide to the Birds prompted the explosive growth of modern birding. Spirited and compulsively readable, Of a Feather celebrates the passions and achievements of birders throughout American history.”

If it weren’t for the fact that this author had already impressed me, I would not have picked up this book. I’ve read too many dry tales of early ornithologists. But Of a Feather is exceptional and a treat to read.

—Roger Lederer

The Help (Kathryn Stockett)

The year is 1962. Miss Skeeter Phelan has graduated from Ole Miss University and returned home to Jackson, Mississippi for the summer. Her mother is nagging her to find a respectable job and/or a husband. Being a writer is Skeeter’s aim—to her mother’s dismay, much more important than a husband.

To escape her mother’s criticism Skeeter gets a job writing the household hints column for the local newspaper, this despite the fact that she has never done even one household chore. She turns for help to the Black maid of one of her best friends. From this unusual relationship comes Skeeter’s idea for a book: What do Black women think of the white families they work for? Skeeter at first does not realize how dangerous her project will become—both for her and the Black maids she enlists to share their stories. But at least such an idea fits what an editor at Harper & Row has told her:

“Don’t waste your time on obvious things. Write about what disturbs you, particularly if it bothers no one else.”

So this is the premise of Kathryn Stockett’s debut novel. Skeeter is writing a book about Black maids in the South in the 1960s, a book to be titled The Help. Stockett is writing her novel (The Help) about Skeeter’s experience. This double layer gives the novel extra complexity: When is Skeeter speaking? When is Stockett? And why did each choose that title?

For Skeeter, it’s because that’s how she naturally views maids, including her family’s “help” Constantine, nanny as well as maid, who raised her from birth. These women are not defined by their characters or their spirits, but by their general job description. Stockett’s identical title choice is not so naïve. Rather, she is examining how White families of Jackson, Mississippi (and many other Southern families of that era) viewed their servants. Not as individuals worthy of respect and concern but as solutions for a family’s needs—“the help.”

What does it mean when we reduce people to their function? In Stockett’s novel, Skeeter is astonished to discover that Aibileen—the first maid to help her—has read Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, a book she herself has not yet read. We learn about another maid, Minny, who twice saves her boss’s life even though originally she had no respect for this woman, who she viewed as lazy white trash. These invisible women, “the help,” and others like them are brave enough to risk their jobs and even their lives to tell their stories. Skeeter’s book powerfully supports their individuality. Even though they must remain anonymous, they are no longer just “the help.” Ultimately, this is the message of both books.

—Jo Ellen Hall

The Ecology of Hope (Ted Bernard and Jora Young)

Hope and Hard Times (Ted Bernard)

Two books “speak to my condition” as a person who cherishes both the earth’s natural webs of meaning—creatures, forests, rivers, and seasons—and its human inhabitants.

In the first book, The Ecology of Hope (1997), authors Ted Bernard and Jora Young seek out and report on inspiring developments in eight locations across America where communities have undertaken to “Collaborate For Sustainability,” as their subtitle declares. The narratives are compelling, well written, and accessible. Extra helpful are the maps.

Eight collaborations, from Monhegan Island, Maine and Menominee, Wisconsin, to Chicago and northern California, show how groups holding differing views and values and conflicting agendas somehow manage to sit down around a table of “gathered stakeholders to put aside historical differences, to work collaboratively, and to arrive at decisions consensually.”

The inclusion of a foreword by Wes Jackson signals the holistic sensibility adopted by Bernard and Young in their study. Two of the eight situations they report on are literally “up the road” in northern California: the Mattole Watershed on the “lost coast” of Humboldt County and the by-now well known efforts of the Quincy Library Group (loggers and environmentalist) to talk across economic and ecological interests toward collaboration. Jackson says the stories reported here “describe small and modest efforts—exactly the requirement for getting something done.” The authors’ informed and sensitive work in the field lays a solid foundation for the thesis of their book. Including epigrams and brief quotations by eloquent poets and thinkers enriches their narrative immensely.

The second book, by Bernard alone, follows up on the earlier study and reports on some added ones. Hope and Hard Times (2010) reports Bernard’s sober appreciation of the complexities and accidents that test the hopefulness and tenacity of good-hearted agents of change “when faced with ‘perilous voices’ of destruction, angry protests and legal action.” The agents of change Bernard values are “an unexpected collection of everyday Americans—folk from the nonprofit world, householders, working people, business people, bankers, farmers and ranchers, Native people, local government folk, even resource professionals from federal and state agencies.”

He is clear-eyed about the challenge of remaining hopeful given “the incredibly volatile situation in which we seem trapped: a scary combination of ticking environmental time bomb and a world financial meltdown.”

“My own sense is soberly sanguine,” Bernard confesses. “It derives not only from the hearts and works of the people in these stories but also from my long engagement with young minds who continue to come up with brilliant ways to tackle problems bequeathed by my generation.” He draws hope from “such visionaries as Henry David Thoreau, John Muir, Rachel Carson, Aldo Leopold, and, I will say, some of the unheralded dreamers in the stories that follow.”

Dreams are what we live on, what impel us up the road to better, healthier ways of living on the land, with the land. Castles in the air? That’s where they belong, Thoreau reminds us in Walden’s concluding chapter; “Now put the foundations under them,” he advises.

—David Wilson

Money and the Meaning of Life (Jacob Needleman)

I know, I know. What a grinch I am to even bring up the subject of money in December, the height of America’s materialistic merry-making. Hasn’t it been a rough enough year already money-wise? you no doubt ask.

Well, yes, it has been rough for some of us, including me. That’s precisely the reason for mentioning this book, and doing it now. Money and the Meaning of Life by Jacob Needleman, published 20 years ago, offers some precious insight into where western civilization went so wrong in weighing up the relative worth of money and meaning. Not knowing, then, what we now know—again—about this country’s eagerness to dive headlong into greed, Needleman is free to explore the underlying reasons without having to spend half the book on current events.

You might blame it on the Protestant Reformation—or what came after, to be fair about it, how those new ideas played out culturally. This territory is probably old hat to many of you, but science and English major that I am, it was news to me. Good news, really, because his explanation makes so much sense. It’s not as if western values only recently became unhinged.

As Needleman explains it, early medieval Christianity was clear on the concept that money and material concerns were not evil so much as they were secondary, commerce being a natural outgrowth of man’s interdependent community relationships. But to value money beyond that—and to seek to acquire vast wealth, to view oneself as autonomous and self-sufficient—demonstrated the sin of pride, believing that one could live without breathing “the air of God.”

Protestants put forth the radical notion that humanity no longer needed to pay homage or bow down to earthly spiritual institutions and their rules. People could instead be guided by their own reason—and the word, the Bible, which believers could read and interpret for themselves. The whole world was declared holy, and any man’s calling in life as sacred as any priest’s. Money, along with whatever one’s work was in the world, were the tools of holiness. In Protestantism money and one’s work in the world were intended to be servants of the spiritual.

Yet the material separated from the spiritual yet again. Modern capitalism, science, and psychology all grew from this new, reason-based spiritual root. According to Max Weber, early twentieth-century sociologist, this new form of Christianity was partially responsible.

There’s more here, too, much more, from Maimonides to samsara. If you can find this book, I highly recommend it for kick-starting some deeper thinking about connections between the spiritual and material. If you can’t find it, maybe I’ll lend you my copy.

—Kim Weir